Rick Blaine: Hemingway’s Wounded Expat Meets the Hard-Boiled Knight of Noir

I’m participating in a group watch of Casablanca tonight, so I thought I’d do a short-ish post about Rick. My Lit wheelhouse is American literature in the first half of the 20th century, so his literary origins are something I always found really interesting.

There’s a reason Rick Blaine has become one of cinema’s most enduring characters. On the surface, he’s just Humphrey Bogart in a tuxedo, running a nightclub in wartime Casablanca, tossing off wisecracks and pouring bourbon. But scratch the surface and you find a character stitched together from the cultural DNA of the early 20th century: the Lost Generation of Hemingway’s novels, the hard-boiled detectives of Hammett and Chandler, and an undercurrent of philosophical Stoicism that gives his story its moral heft.

In other words, Rick is not just a character in Casablanca—he’s the culmination of two decades of literary and cultural archetypes converging on the big screen in 1942. To understand him, you need to see him as part Hemingway hero, part noir detective, and part reluctant Stoic sage.

The Wounded Expat: Hemingway’s Lost Generation

Before there was Rick, there was Jake Barnes. Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926) defined the archetype of the disillusioned expatriate. Jake is an American journalist living in Paris after World War I, drinking too much, haunted by a war wound that left him impotent, and hopelessly in love with Brett Ashley, a woman he can never truly have. [It’s really much more complicated than that, but entire books have been written about Jake and Lady Brett.]

Sound familiar? Swap Paris in the 1920s for Paris in the late 1930s, and Brett for Ilsa, and you essentially have Rick’s backstory. In fact, Casablanca almost feels like a sequel to The Sun Also Rises: what if Jake Barnes had left Paris and set up shop in North Africa, still cynical, still drinking, and still carrying the ghost of an unattainable love?

Like Hemingway’s characters, Rick lives by a code. Hemingway’s so-called “code hero” is defined not by triumphs but by how he endures loss and pain with dignity. Jake Barnes cannot have Brett, but at the end of the book, he accepts it with a quiet, heartbreaking grace: “Isn’t it pretty to think so?” Rick follows the same path. He can’t have Ilsa, but instead of clinging to her, he lets her go—because it’s the dignified, necessary choice.

There’s also Frederic Henry in A Farewell to Arms (1929), another American in Europe, another love story shattered by war. Frederic’s acceptance of Catherine’s death at the end mirrors Rick’s stoic acceptance that Ilsa will never be his. The emotional logic is the same: war and history have rendered private happiness impossible. The only honorable response is endurance.

Rick is a Hemingway hero translated into Hollywood. He drinks heavily, he is emotionally scarred, he hides his pain behind irony, and when the chips are down, he acts not for himself but for a higher principle.

The Hard-Boiled Mask: Hammett and Chandler

But Rick isn’t only Hemingway’s exile with a hangover. He also borrows heavily from the American noir tradition that exploded in the 1930s and early 1940s. Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (1930) introduced Sam Spade, the archetypal hard-boiled detective: cynical, tough, and morally ambiguous. Spade may sleep with his partner’s wife, may manipulate everyone around him, but when faced with the choice between love and principle, he sends his lover Brigid O’Shaughnessy to prison because “when a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it.”

Rick Blaine makes the same choice. He could run away with Ilsa, but instead he sends her on the plane with Victor Laszlo, because there’s a higher code at stake. It’s the same moral geometry: personal happiness must yield to principle.

Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, introduced in The Big Sleep (1939), refines this archetype. Marlowe is witty, cynical, always ready with a sarcastic quip, but underneath he’s a knight-errant in a corrupt world. He might take money from dubious clients, but he won’t betray his sense of decency. He’s a romantic at heart, hiding behind a mask of sarcasm.

That’s Rick all over. When we meet him, he’s insisting he “sticks his neck out for nobody.” That’s classic noir tough talk, the same kind of thing Marlowe would mutter to keep the world from seeing his softer core. But over the course of the film, Rick reveals that he does care. He’ll risk everything for Ilsa, for Laszlo, and ultimately for the fight against fascism. The mask drops, and we see the knight underneath the cynic.

Rick’s nightclub even functions like a noir detective’s office. Everyone comes through with their problems, their scams, their hopes for escape. Rick stands at the center, watching, assessing, keeping a ledger of debts and favors. He’s not technically solving mysteries, but he’s inhabiting the same role as Spade or Marlowe: the moral weathervane in a corrupt world.

Stoicism in the Fog

Layered on top of Hemingway and noir is a philosophical streak that gives Rick his gravitas: Stoicism. The Stoic philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome—Epictetus, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius—argued that we cannot control external events, only our responses to them. Virtue lies in mastering one’s emotions, accepting fate, and acting in accordance with reason.

Rick is practically a Stoic case study. He cannot control Ilsa’s marriage to Laszlo, or the fact that the world is at war. What he can control is how he responds: with dignity, with restraint, with virtue. When Ilsa tells him she still loves him, Rick doesn’t rage or crumble. He simply accepts the reality and chooses the higher good: 'The problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.' That’s Marcus Aurelius with a glass of bourbon.

The Hays Code and the Casablanca Love Story

It’s impossible to fully understand the Rick/Ilsa dynamic without considering the Hays Code, Hollywood’s strict moral guidelines in force from the 1930s through the 1960s. The Code forbade the glorification of adultery, required that marriage be depicted as sacred, and demanded that virtue triumph over passion. This had a profound effect on Casablanca.

If the story had been told without censorship, there’s every chance Rick and Ilsa might have ended up together—or at least shared a more openly passionate romance. But under the Hays Code, Ilsa had to remain loyal to her husband, Victor Laszlo, the moral paragon of the film. Even if audiences longed for her to choose Rick, the script could not reward an adulterous relationship. The foggy runway scene is thus a compromise: Rick and Ilsa’s love is acknowledged, but it must be sublimated to duty, marriage, and the war effort. The very structure of the story owes itself to censorship, which forced writers to sublimate passion into sacrifice.

Paradoxically, this restriction may have made Casablanca greater. By forcing Rick and Ilsa’s love into the realm of the impossible, the film transformed a melodramatic romance into a mythic parable of sacrifice. Their story became timeless precisely because it could not resolve into conventional happiness.

Why Rick Resonates

The genius of Rick Blaine is that he’s not just one archetype—he’s the convergence of several cultural streams: Hemingway’s Lost Generation, noir’s hard-boiled knight, and the Stoic philosopher. Each element alone would make a strong character. Combined, they make Rick timeless.

And let’s not forget the historical context. Casablanca premiered in 1942, just after Pearl Harbor, when America had finally been dragged into World War II. Rick’s transformation—from isolationist cynic to committed anti-fascist—is not just personal. It’s national. He embodies America’s reluctant entry into the war. His story is America’s story.

Conclusion: The Stoic in the Tux

At the end of Casablanca, Rick doesn’t get the girl. He doesn’t ride off into the sunset. He lights a cigarette, makes a joke, and walks into the fog. It’s not the ending Hollywood usually offers, but it’s the only ending that makes sense for a character built from Hemingway’s wounded expats, Hammett’s hard-boiled detectives, Chandler’s knight-errants, and the Stoic philosophers of antiquity.

Rick Blaine endures because he is all of them at once. He is the romantic who sacrifices love, the cynic who reveals his idealism, the exile who finds purpose, the Stoic who accepts fate. He is every disillusioned man of the twentieth century rolled into one—and somehow, against the odds, he makes it look damn good.

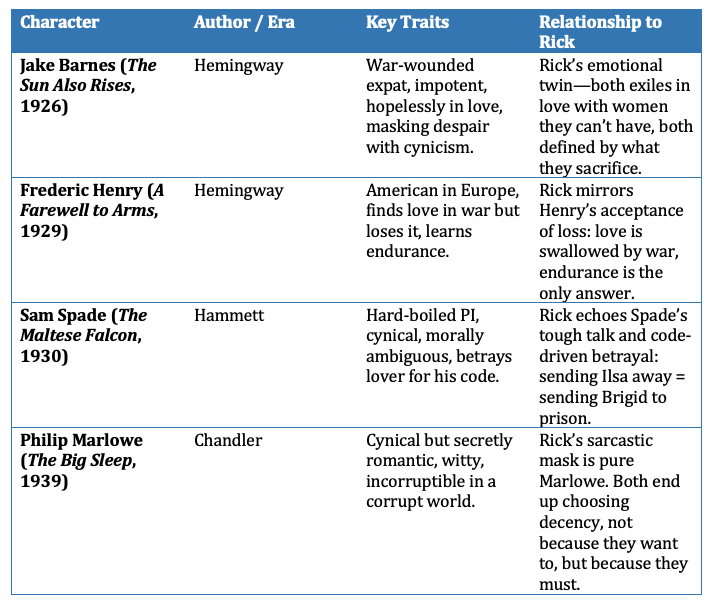

Rick vs. His Literary Cousins: A Comparison